Election Day Communion and the End of Embracing

We hoped communion could bring a fractured nation together. How quaint.

Does anyone remember Election Day Communion?

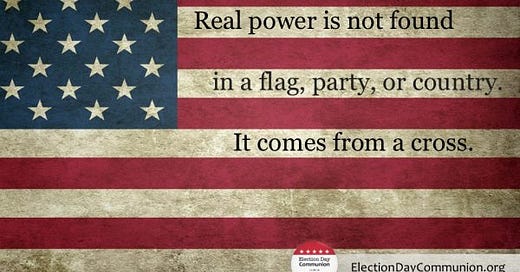

It was a movement in 2012 for churches to have communion services on or around election day. As people were choosing to either re-elect President Barack Obama or elect then-Governor Mitt Romney, the movement was calling people to unity around the communion table and ultimately Jesus Christ. Started by mostly Mennonite pastors, the movement wanted to combat the political divide with something that united people regardless of party: communion. They described their desire this way:

Election Day Communion began with a concern that Christians in the United States are being shaped more by the tactics and ideologies of political parties than by their identity in and allegiance to Jesus.

Out of this concern, a simple vision sparked the imaginations of several Mennonite pastors: The Church being the Church on Election Day, gathering at the Lord’s Table to remember, to practice, to give thanks for, and to proclaim its allegiance to Christ.

I remember participating in this four years later. I worked with a friend who pastored a Presbyterian congregation nearby and we had a communion service the night before the election. It was a wonderful service.

It’s interesting that this was the night before Donald Trump won the presidency, because after this shocking event everything changed.

Election Day Communion came about during a time when the goal was to bring people together. There was a lot of talk of unity and coming together around a communion table. Looking at the churches taking part in 2012, it was a mix of evangelical and mainline Protestant churches. I think as much as people were concerned about polarization back then, there was still hope that we could come together.

Presbyterian Pastor Adam Copeland wrote the following on his blog that later appeared on Christian Century:

With this in mind, after I cast my vote, I plan to meet at the Lord’s Table to be reminded of greater priorities, repent of my sin, and be sent to embrace my faith’s higher calling. I look forward to participating in our local Election Day Communion.

Looking at the old Election Day Communion website and reading this old blog post by Copeland is like reading a letter from a century ago. The rise of Donald Trump and hyperpartisanship has coarsened our politics, making the hope we could be united by communion seem rather quaint.

It seems especially quaint after January 6 and the prominence of Christian Nationalism and those two events seem to have killed Election Day Communion. Their Facebook page hasn’t been updated since 2020. I haven’t heard anyone bring it up this year.

Election Day Communion is gone and what has replaced it is Our Confession of Evangelical Conviction. This came out a few weeks ago. While it is also about politics and polarization it’s a little different. Instead of a specific event, it is a statement that religious leaders can sign. It is a document developed in the shadow of Trump and MAGA. Reading the letter, it felt very familiar. That was on purpose; it is based on the Barmen Declaration, a confession spearheaded by theologian Karl Barth, as Hitler became the German Chancellor and the advent of “German Christians” who were aligned to the Nazis.

If Election Day communion was about bringing people together, Our Confession of Evangelical Conviction is about drawing lines and taking sides. Conviction instead of Communion.

As the Confession went around recently, I hesitated to sign it even though I believe in most of what it says. While MAGA populism concerns me and Trump’s authoritarianism gives me pause, it just felt depressing to sign it. Maybe others are eager to pick a side and stand on the “right side of history,” but I’m not. If we are signing a document that is based on a historic confession during one of the most genocidal regimes that ever existed, it doesn’t say anything good about the times we are living in.

I understand the need for the Confession. I understand the need to sign it. I don’t think Donald Trump is Hitler (as Jonah Goldberg has said, Hitler would have repealed Obamacare), but that doesn’t mean having him in the Oval Office is no big deal. It doesn’t mean people around him are harmless. But even with all that I am sad that we are in a time when we feel we must choose sides. Good here, bad there. I’m sad about what we are losing.

I have signed the Confession. We are in a desperate time and sometimes you have to pick sides. But I wonder what happens after the election, especially if Kamala Harris wins. Will we move from conviction back to communion? Can we work to piece together a nation torn asunder by polarization?

I’ve heard the third chapter of Ecclesiastes more times than I can count. I’ve always wondered why it said things like a time for hate and a time for love. Isn’t it always a time for love, I used to think. I don’t think there is ever a time to hate people, but there are times we hate systems that can oppress and hurt people. But even more so in this context, in the second half of verse 5 it says there is “a time to embrace and a time to refrain from embracing.”

The years of Election Day Communion were a time of embracing. Communion is a time to come together and embrace in spite of our differences. The Confession is a time to refrain from embracing. This is a time to declare our allegiance to Christ to not embrace as much as define who we are and stand apart from the crowds tempted by nationalism or racism.

I want to get back to the time of embracing, but in a time when a former President is telling lies about legal refugees, now isn’t the time.

But may we hope for that time when we can embrace through communion again.