My Dad who died in 2015 once told me a story that I’ve shared a couple of times on the interwebs about what life was like when he was young.

In 1953, Dad moved from his native Louisiana to Michigan to start work in the auto plants. He ended up working at Buick in Flint, Michigan until he retired in 1992. Back in the 50s, he would occasionally head back home to see his mother. My aunt, his sister would make her wonderful fried chicken for him to eat during his trip. On the way back, his mother would do the same thing. Did they do this because it was being spendthrift? No. The reason they did this is because in 1950s America it wasn’t so easy for a black man to stop and eat a restaurant, especially in the South.

When Dad was tired he pulled over and rested until a cop told him to move along. Again, it was impossible for a black man in the 1950s to get a room in a hotel.

By the time I came around in 1969, things were changing. That was even more so when Mom, Dad, and I drove from Michigan to Louisiana in the 1970s. We could eat in restaurants. We stopped and stayed in hotels. But for Dad, the change wasn’t easy. My mother would tell the story where we stopped one morning for breakfast in Vicksburg, Mississippi. Dad didn’t want to go into the restaurant, afraid of what might happen if we entered. Mom insisted the laws had changed, but he didn’t trust that things could change. Mom and I ended up getting breakfast in the restaurant (where Mom said the waitstaff cooed over my cuteness) and getting a meal to go for Dad who stayed in the car. While the laws had changed, it would take some time for Dad’s mind to accept that change.

Over at the hellscape that is Twitter these days, this picture has been going around:

The tweet that shares this photo then says, “The world of our grandparents.”

Now, it’s pretty obvious this is an AI-generated image. The street is impossibly narrow and the signs are filled with gobbeldygook. Looking at the account who posted this, the gentleman seems to be a Christian Nationalist who longs for some kind of idealized past that we no longer have.

But the past is never as neat or idealized as we want it to be because it is filled with sinful humans. That doesn’t mean the past has nothing to teach us, but it does mean the past is complicated. As the theologian Billy Joel says in his song “Keeping the Faith,” “The good ‘ole days weren’t always good, tomorrow isn’t as bad it seems.”

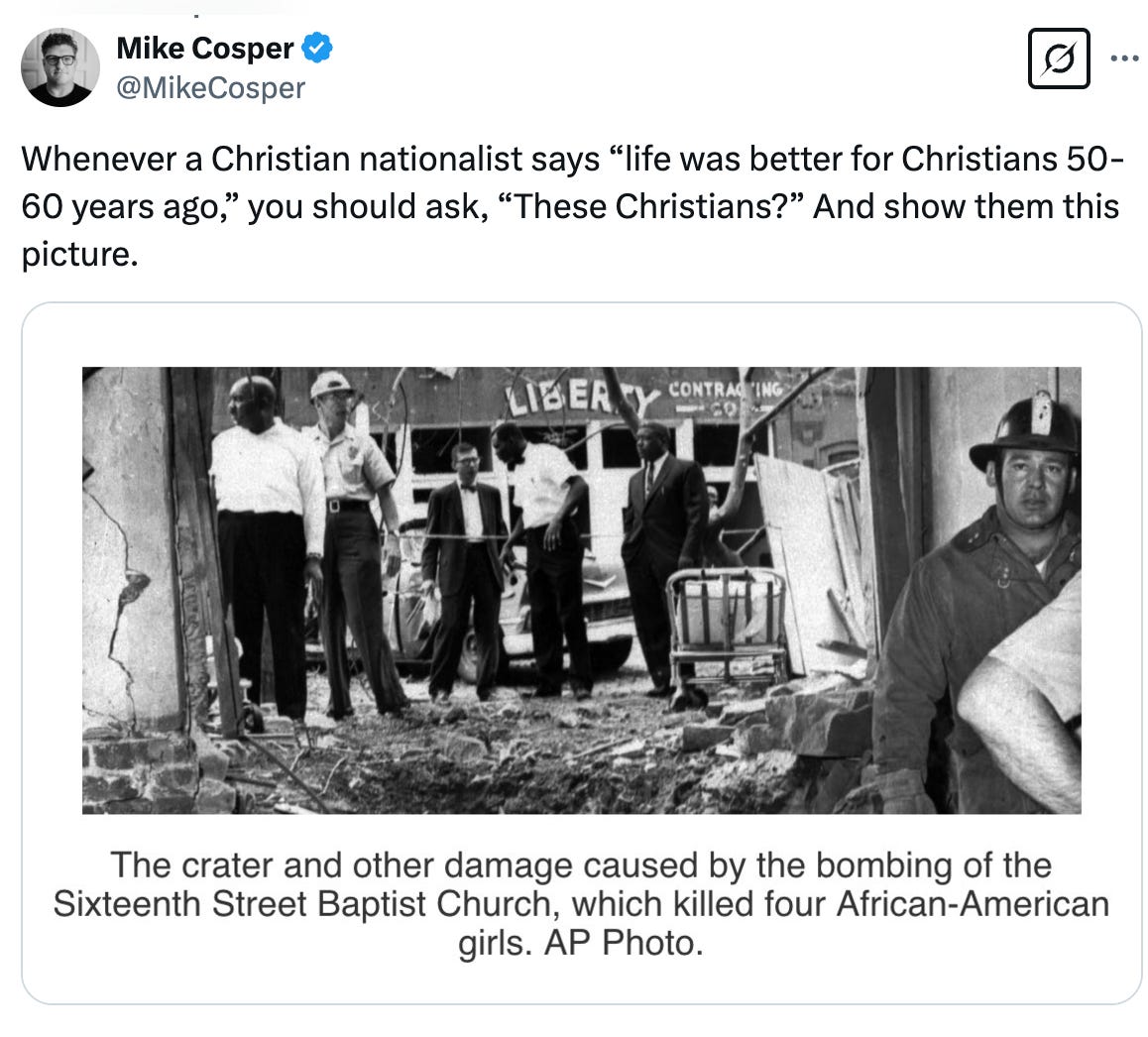

To put a fine point on it, the past wasn’t always great for whole swaths of people like my father. Christianity Today’s Mike Cosper puts it in stark relief:

Nostalgia isn’t all bad. As someone who is now in my mid-50s, it is hard not to look back at my days as a teen when life seemed a lot more simpler.

But as the above example shows, nostalgia can have a dark side and can lead to sin. I’m not going to automatically assume that the poster of this is a racist, but wishing for this simplified past ignores that for many the past wasn’t so good, especially for people of color or LGBT persons. Let’s be honest here: looking at the past in such a way can cover up the sins of the past. Were there good things about the 1950s? Yes. Nothing is all good or bad. But nostalgia is kind of like a drug; a little might be okay, but a lot of it can be toxic.

Writing during the height of the COVID pandemic five years ago, Jeremy Sabella wrote about how the lockdowns of the time had people pinning for the “before time.” He then relates this desire for nostalgia to the Israelites in the wilderness and their desire to go back to Egypt, you know the place they just left. Where they were enslaved. Why were they so willing to worship a golden calf when they saw God acting so mightily before them?

Sabella says nostalgia overwhelmed them. The drama of the Red Sea crossing was in the past, and the uncertainty of life in the wilderness set in. Next thing you know they were collecting earrings to make a new god. The Israelites were created a distorted past that had grave consequences:

The golden calf debacle was the product of willful misremembering. The house of Israel understandably missed the familiarity, the routine, and the other good aspects of the life they had built in Egypt. Their old world was gone, and their new world was a wilderness of uncertainty. But nostalgia so consumed them that they overlooked 400 years of bondage and broke the first and second commandments in order to conjure an idealized, distorted past. They lost their moral bearings so completely that God considered wiping them out before Moses intervened (Ex. 32:11–14).

Sabella talks about how nostalgia is focused on the past, an idealized past, but the past nevertheless. The past isn’t just idealized, but it is idolized. It isn’t about trusting God as we move forward into uncertainty, but putting our trust in God as we venture into this unknown. When I think back to my Dad, he was afraid of the past and found it hard at first to trust an uncertain present. But over time, he learned to trust that the change was real. He could have hope in the future because he could trust the present.

Instead of looking for nostalgia, we have to have hope. Hope is something that looks forward to the future, and trusting in God. We have hope that God will be with us as we walk into the unknown.

The past has things to teach us, both good and bad. But let’s not make the past our god. Let’s not idolize the past and ignore how the past hurt others, sometimes at the expense of the good life. And let’s have hope in the unknown future where God is with us.

This podcast and newsletter is a labor of love. It’s free to everyone, but there are costs associated with making this podcast available. Would you consider becoming a paid subscriber? It’s $5/month or $60/year. Thanks!

I always say, the 1950s tax structure and infrastructure and blue collar job security, plus women's liberation and racial equality, would be a worthy goal. But we all hear 1950s and think of only the bad or only the good. We are not bright people.