Back in 2012, I wrote a short blog post in the aftermath of my Uncle David dying at the age of 60. I heard several what could have been called trite sayings at the funeral. Here’s what I said back then:

David was an active of an Apostolic church in nearby Sanford. As we went to the viewing at the funeral home and the next day at the church, I came to face to face with all those cliches you hear when someone dies. “God is in control.” “He’s not in pain anymore.” “This all happens for a reason.”

My seminary-trained brain tells me I’m not supposed to accept such trivial sayings. I’ve learned that such words just cover up the pain that people are really going through. I’m supposed to see such sayings as a twisting of theology and incredibly insensitive to those suffering.

I know that’s what I’m supposed to think.

But now I don’t mind hearing them. Not after dealing with what I’ve dealt with.

After hearing my mother, who is nearly 20 years older than David, wail at the loss the boy she helped raise- after seeing my cousins and my Aunt deal with the indescribable, I really don’t have a problem with people trying to offer some words of hope-even if they are cliches.

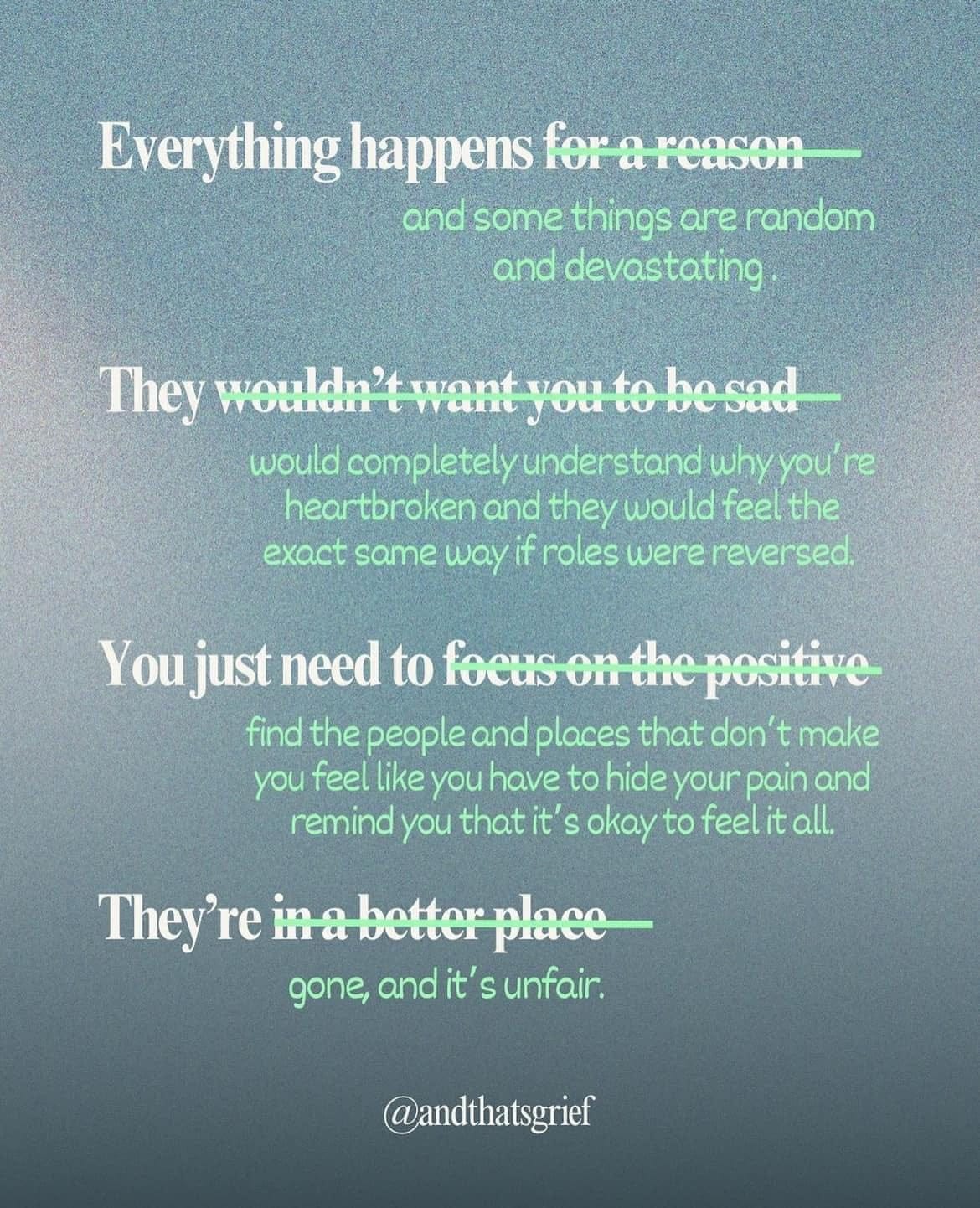

I thought about this article again after seeing this meme that seemed everywhere on Facebook this week:

I’ve never liked those “there, I fixed it” memes and this one was no different. It was the last one that bothered me the most. It’s bad to say they are in a better, place and instead, you should say that a loved one is gone, and damn unfair.

The problem with the last sentence is twofold. First, it seems that it must be a binary choice: either/or. But what if it’s both/and? Can someone be in a better place AND also feel the loss?

The second problem is personal. As many of you might know, my mother suffered a stroke in July 2023. She died in February 2024. The last 2-3 months of her life were terrible. It was hard to see her decline and to see her strong spirit silenced by the neuropathic pain that tormented her. I was there as I saw her draw her last breath. As painful as that was to witness, I knew that as a Christian, death wasn’t the last word. I knew that she was now in a better place. A goddamn meme written by an idiot who thinks they wrote the wisest shit ever will not speak for me and tell me how I can f-ing grieve.

My mother is gone and it is painful. It does feel goddamn unfair. But I also believe she is in a place where there is no more crying and no more dying. I believe that she will rise again on the last day with a new body.

The problem with the saying “They’re gone and it’s unfair,” is that there is no hope in such a sentence. All that’s left is a gaping hole and nothing else. I’m not saying that as a Christian everything is all sunshine with unicorns that poop rainbows. People still die horribly. But the thing that makes the grief a little less painful is that I know there is hope even in the midst of grief. I may not get rainbow-pooping unicorns, but there is a promise that I will see her and my father again.

If we look beyond the memes, Christians live in what has been called the “now and the not yet.” We live in hope. We live believing in the resurrection. It is the not yet. But in the now, we live in the pain of death. It is both hopeful and devastating at the same time.

Bryan Lilly, an Anglican deacon wrote recently about how he faced his mother’s death a few years ago. He shares how much the passage from 1 Corinthians where we hear about death swallowed up in victory and wondering where death’s sting is now. It was always a wonderful verse for him but life taught him it how the promise rings hollow for now:

We often reach for this beautiful passage for comfort, and rightly so. But the sting of death is only truly removed for the dying Christian, whose death becomes “the gateway to everlasting life.” Death’s head has been crushed in Christ’s death, resurrection, and ascension—but its body still convulses until Jesus returns. For those of us who experience the loss of a loved one, death’s sting remains in the form of grief.

For Lilly, in the space of a few weeks, his mother went from an emergency room visit with congestive heart failure to a heart attack and death. All the while he was using the Book of Common Prayer for guidance during this challenging time. He prayed the Daily Offices with his mom for several days. The prayers got him through the time, but it never removed the sting of death:

Visits to my mom’s bedside fell into a rhythm. I would hold her hand, kiss her forehead, tell her I love her, and then pray the Morning, Midday, Evening, or Compline offices out loud, depending on the time of my visit. When the rubrics invited me to offer intercessory prayers, I reached for the collects for the sick (BCP 2019, pgs. 231-235). Since Mom spent her final weeks unresponsive or sedated, I don’t know if any of these prayers registered with her. Yet, I prayed they would bury themselves deeply beyond the veil and into her heart, mind, and affections.

On the day the machines were turned off, I held Mom’s hand, kissed her forehead, and told her I loved her as I often had. Then, over my mom, I prayed the Ministry to the Dying for the first time as a minister in the Anglican Church.

I’d like to tell you that, by praying with the Book of Common Prayer, I would go home each night during those weeks with peace beyond understanding. I didn’t. They occasionally gave me a sense of peace, hope, and comfort, and I am thankful for those moments. However, the Book of Common Prayer did not remove the sting of Mom’s suffering and death or the following grief. It did carry me through it. The liturgy prayed for me when my own strength failed—just as it is meant to do in such moments.

I did a lot of reading of the Psalms to Mom in her last few months. I don’t know if it made either of us feel better, but it was a prayer when both of us were prayed out.

Last week, I was at my “tentmaking” job as a communications specialist at a Lutheran congregation north of Minneapolis. One of the church members was busy getting the church library ready for an open house. She asked how I was doing, and I was honest to share where I was. She talked about her own mother’s passing decades ago and then shared after all she had went through, the good thing was she was no longer in pain.

I could very well have been upset about all of this, but it was strangely comforting. These were the words I needed to hear at that moment. I needed words of hope and God spoke through this woman to offer those healing words.

Maybe that meme helped people, but it didn’t help me. At the end of the day, I need hope that death isn’t the last word and I believe in the God that tells me what no meme could tell me, that my mother is in a better place and that one day she will rise again when death is defeated.

She is in a better place and that’s good. She is also gone and it is not fair.

All of this is life and God is in the midst of it.